The following is a feature article from ADSC – The International Association of Foundation Drilling about Tri-State Drilling. We are grateful for their thorough dive into our company and for the feature. Please enjoy this in-depth look, or contact us if you have any questions.

Written By Peggy Hagerty Duffy, P.E., D.GE, ADSC Technical Adviser

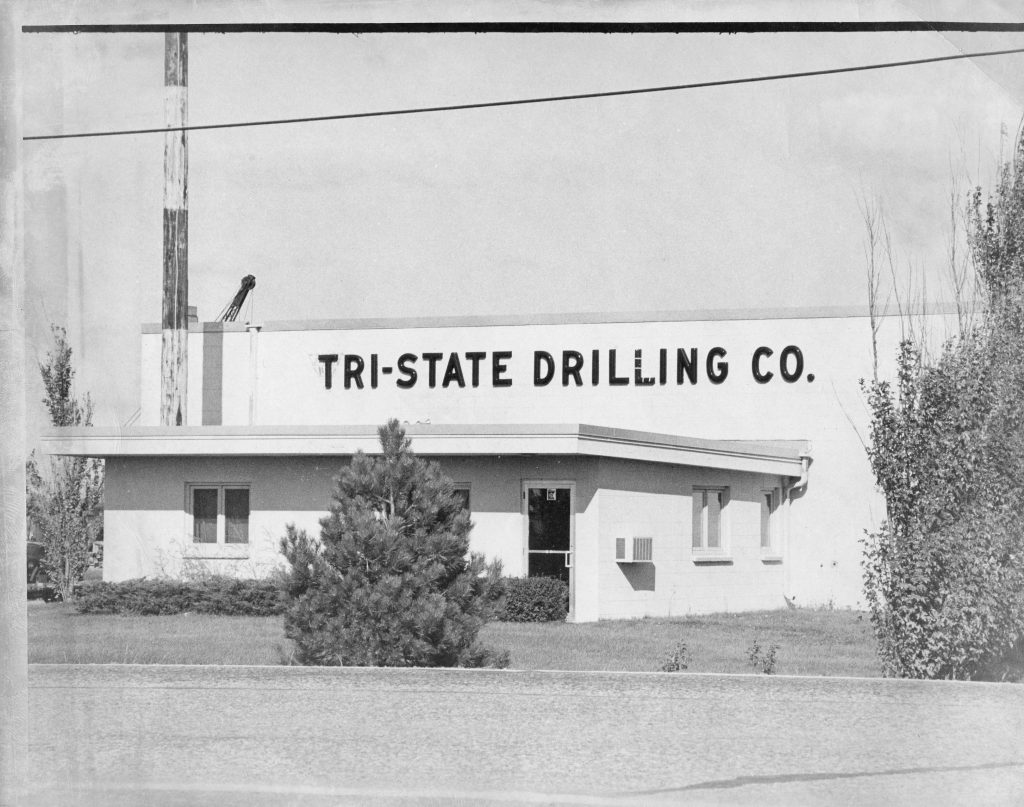

Families are complex and diverse. Family-owned businesses are affected by the intricate dynamics and characteristics of each group and often succeed or fail based on genetic commonalities and individual personality differences. Tri-State Drilling, of Hamel, Minnesota, was begun by not one, but four families. and the harmonious state of this successful company is due to their differences as much as their similarities.

Founders

Each of the four company founders (Bob Melcher, Wayne Riethmiller, Clarence Berthiaume, and Ralph Eisele) came into the endeavor with a different back-ground, a unique set of tools, and a subtle variation on the goal of doing business a new way. All four possessed a solid, Midwestern work ethic, an eventual building block to their success. Every subsequent chapter in the Tri-State story has had this core value as a constant thread.

Bob Melcher was a pump salesman who graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1944 with a degree in mechanical engineering. He began his career at Pratt and Whitney, in Connecticut, working on aircraft engines, and had provided mechanical support in Guam during World War II. Bob moved back to Minnesota to work for Layne Minnesota, a pump supplier and well-drilling company. Bob’s work at Layne consisted primarily of bidding for municipal projects. At the time he had three young children, John, Kathy, and Mary Kay, with his wife, Lorraine, a redhead so lovely he had asked her name when he saw her in a drugstore one day.

Wayne Riethmiller was a civil engineer who had moved west from the mining country of Martins Ferry, Ohio. After graduation from Ohio State University, he worked on drilling wells in several ventures. He was involved for a short time in the Washington, D.C. area, dealing with difficult-to-drill clays and low headroom locations. He moved to Minnesota to contribute his drilling experience to the Layne well-drilling operations. Wayne brought with him his wife, Mary Roberta, “Tootie,” who was all too familiar with the drilling business after assisting Wayne with administrative duties on some of his early efforts. They had a young son, Mark.

Clarence Berthiaume was a local descendant of a long line of farmers. He was a skilled mechanic who could repair almost anything, and was happy as long as he was working to keep equipment functioning properly. He also was married to Leona and had three young children: Sandy, Ronnie, and Debbie.

Ralph Eisele came from a family with deep roots in the Minneapolis area. He was a well driller who understood the nuances of rock and soil in the upper Midwest. His education from the University of Minnesota was in the area of forestry, but there weren’t many jobs for foresters in the Minneapolis area in the early 1950s, so Ralph fell back on his experience with well-drilling and irrigation. He went to work for Layne to feed his young family, consisting of his children, Rick, Jeanne, Randy, and Jackie, and his wife, Joyce.

The Beginning of Tri-State

Bob, Wayne, and Ralph experienced several situations in which they deeply disagreed with Layne’s policies and business practices. In the summer of 1955, the disparity in principles became a sticking point. Rather than stay and complain, they decided to leave and start a new business. They were excited about the prospect and determined to work in an environment consistent with their personal beliefs despite a lawyer friend telling them the venture would be a bust.

Characteristic of the civil engineering mindset of stability, Wayne gave Layne twelve months notice, saying he would transition out. Bob, indicative of the mechanical engineering framework of movement, provided his boss with two weeks notice. He and Wayne had seen a project being bid that seemed to be appropriate for their capabilities, so they bid it. When they got the job, Bob turned in his notice, and the boss was furious. Wayne also decided he could not stay the full twelve months. The boss promptly threw both men out and demanded the keys to their company vehicles. Wayne and Bob were sitting on the curb, waiting for their wives to pick them up, when the police drove up and said the boss had called in a report of trespassers. This exit was fittingly final and served as an exclamation point behind their reasons for leaving.

Bob and Wayne knew they would need field and mechanical support if they intended to continue in the water supply construction business. Starting a new business required solid contributors who wouldn’t create uncertainties and add to the many burdens that come along with building a company from scratch. They asked Ralph to leave Layne with them. Clarence Berthiaume was a mechanic who just wanted to repair the equipment. He had worked on equipment with moving parts for years and could be relied on to keep things running. And, Clarence was asked to join the group. Clarence and Ralph brought different attributes to the new company but shared with Bob and Wayne an ability to work hard and a commitment to doing a good job. All four men had young families as incentives to make the business work.

One small family “challenge” occurred immediately. Four-year-old Mark Riethmiller, was upset when his mother told him to clear out his toy room so that the newly formed Tri-State Drilling could move into their first office. Tootie had already been drafted into administrative duties for the new company, and part of her job included removing toy trucks from the office floor, also known as the spare room in the Riethmiller house. Mark moved his toys and bounced back with the typical resilience of a four-year-old.

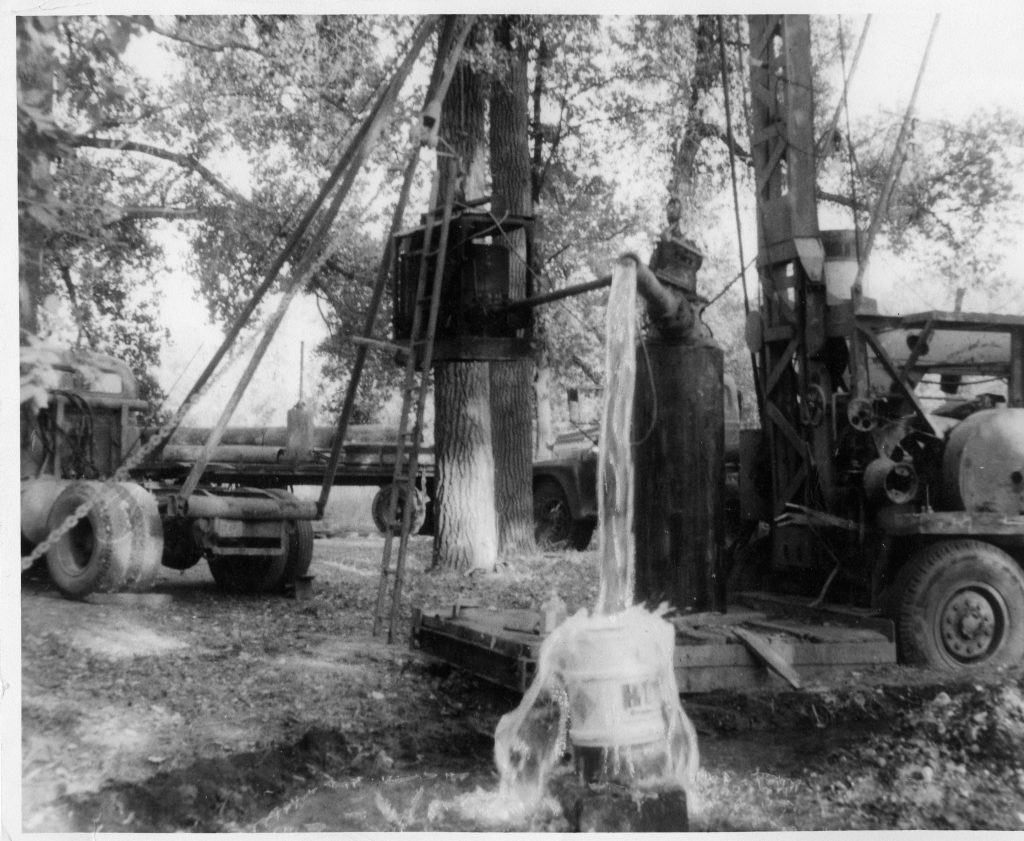

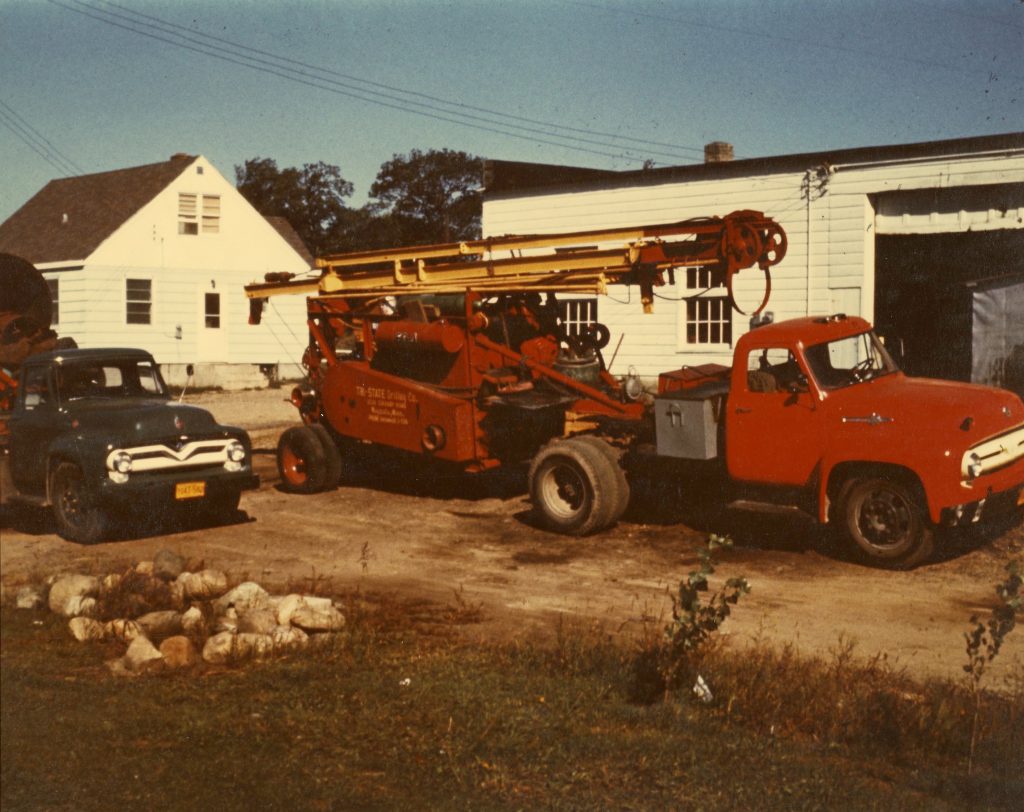

Tri-State Drilling’s first big job involved drilling relief wells for a dam in Montana. They had one month to prepare for the job, including purchasing a water well drill rig. Their first major corporate decision came when the truck hauling the rig blew a tire on the way to start the project. An emergency board meeting was held to decide whether to buy a new tire or a retread (they bought new); the problem was solved, and the company went on to complete its first successful job.

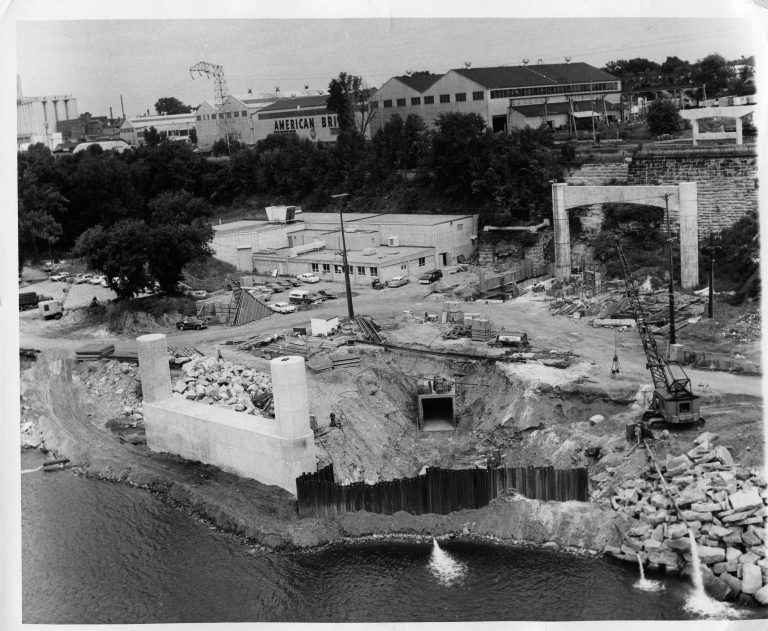

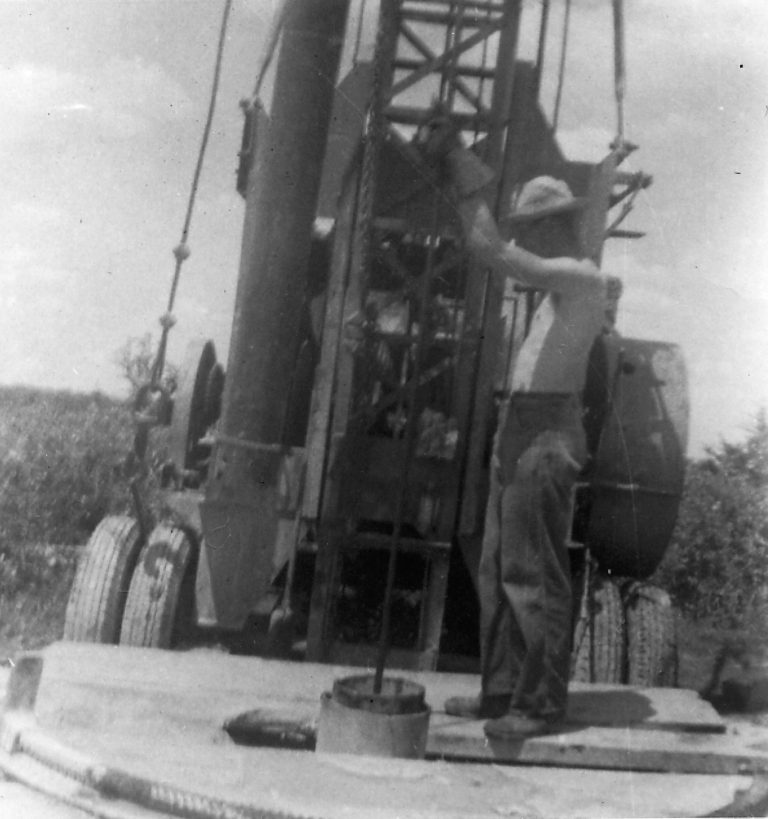

Within the next five years, Tri-State Drilling added rigs (and family members) and became direct competition for Layne. But the men were not satisfied with just playing in one corner of the sandbox. Wayne saw possibilities in the field of construction dewatering; he believed that their in-house understanding of groundwater and their equipment capabilities made the company a perfect candidate for such work. Around that time, the men bought a Watson 5000 crane-mount drill rig to enhance their arsenal. (Tri-State already had a Watson test rig). Modifying their cable-tool rigs also gave Tri-State Drilling a leg up because it greatly decreased the set-up time needed on a job. Most competitors still needed a full-day or up to two work days to get set-up, while Tri-State arrived at the project site and was ready to go within a few hours. This asset proved to be critical as Tri-State expanded into the foundation drilling business, primarily dealing with transmission lines and other utility work. Their concentration on mobility was a boon to project owners who needed their projects completed as quickly as possible through hostile, undeveloped terrain.

Expansion

Not long after the company finished its first job two of Clarence’s brothers, Max and Gene, were hired. These men started as field hands and worked their way into management positions. Additional employees were needed within a short time and by 1965, the company employed 20 people.

As the company continued to expand into a wider geographic area, as well as into additional fields of work, the four men expanded their own personal ventures. Bob and Lorraine had nine children: John, Greg, Kathy, Mary Kay, Anne, Steve, Jim, Charlie, and Rich. Wayne and Tootie had three children, Mark, Marylou, and Marilyn. Ralph and Joyce had five children, Rick, Jeanne, Randy, Jackie, and Janice. Clarence and Leona rounded out the crowd with four children, Sandy, Ronnie, Debbie, and Jimmy.

The environment at Tri-State was centered on family early on. Annual company picnics brought everyone together and were anticipated eagerly by the partners’ children. Although very young Marilyn Riethmiller didn’t understand why her dad came home so dirty all the time, she grew to appreciate his work when he began taking her to the shop to see the forklifts run. The other children went in and out of the business, literally and figuratively, from the start of Tri-State.

Much of the company’s success was a product of their keen understanding of the specific equipment capabilities that were important for certain types of projects. As a result, their relationship with Watson Inc. developed as the company flourished. Wayne wanted an auger rig that was mobile and required minimal set-up time. He contacted Jack Watson with that goal and Jack built the first Watson 3000 based on Wayne’s specific requests. The two companies provided each other with mutual technical support and business development at a time when the foundation drilling business was evolving daily.

Tri-State became an established presence in the foundation drilling and water supply service fields throughout the 1960s and continued on a solid track into the 1970s. Clarence was the first original partner to bow out, leaving the company in 1966. Meanwhile, the many children of three of the men (and of Clarence’s two brothers) were becoming part of the organization. Some were part-time, working at summer jobs while in high school and college, and some were permanent.

Marylou Riethmiller (now Swedberg) moved up through the ranks, beginning as a parts runner and a bookkeeper and climbing to her present position as Chief Financial Officer. Her sister, Marilyn, worked off and on at the company from the time she

was in high school until the present, handling safety matters and company travel. Mark Riethmiller obtained his civil engineering degree and went to work for Tri-State when they opened an office in Houston, Texas in 1982. The office closed in 1985, and Mark worked elsewhere, finally coming back to Minnesota and to Tri-State in 1992, where he stayed until he retired in 2012.

Kathy Melcher continued her bookkeeping work well after high school, and Charlie Melcher obtained his civil engineering degree and returned to the company to manage projects.

Ralph believed that his kids should not work for the company until they were 18 years old, so his sons Rick and Randy only began working in the field for Tri-State after graduation from high school. Rick went on to other pursuits, but Randy came to work full-time after college and a tour of Vietnam.

Membership in ADSC

The 1970s brought two important events to the Tri-State timeline, the company’s membership with the ADSC and the hiring of Larry Gordon, a “powerhouse of the sales force,” according to Jim Melcher. The ADSC gave the company external help by providing them with networking opportunities and by giving technical and administrative assistance with industry issues, such as safety. Tri-State was one of the few ADSC Contractor Members in the upper Midwest at the time.

Much like the Beatles, the fate of the original four partners was a gradually unfolding story. Clarence left to pursue other interests, but Ralph was fully active in the operation until his untimely death in 1983. His wife Joyce retained his shares and stayed in active contact with the company. Randy had worked for the company since 1967 in some form or fashion, and he easily picked up the family mantle to continue the Eisele tradition at Tri-State.

Jim Melcher was one member of the Tri-State family who had not originally intended to return to his summer employer. He thoroughly enjoyed working as a foreman on a crew drilling transmission tower foundations during the summers but his many interests led him to a liberal arts degree and seven months backpacking in Europe and the Middle East. After this, he returned to the United States, where he went to work for a financial newsletter in Minneapolis. The job turned out to be a nonstarter, but it proved to be a success in his personal life. Ruth was an editor at the publication, and she and Jim would go out to lunch to laugh about the crazy happenings in the office every day. The craziness led to both of them leaving the business, but the laughter led to a year of dating and marriage in 1984.

The U.S. economy had slowed in the early 1980s, and Tri-State had slowed its progress, as well. The two remaining partners both knew they needed to plan for the future, but they were not certain of who would lead the company into the next era. Bob knew of the instability of the newsletter where Jim worked, so he called and asked if Jim would come back, ultimately to be part of management. Bob and Wayne knew successful steering of the business would require an intimate knowledge of the work itself, so they told Jim he would have to spend a year in the field. More than two years into that year, Jim had almost had enough. The partners were sympathetic to his pleas and relented, bringing him into the office. Bob had attended an ADSC meeting in which a presentation was made on using computer software for construction management. This new development showed the ‘old dogs’ there were new tricks to be learned, and Jim would help them do it.

Tri-State exercised their talents in mobility when cell tower networks were being built out in the 1990s and early 2000s. They expanded their reach to well beyond the upper Midwest, but continued to maintain the company policy of using Tri-State employees on these far-flung jobs, hiring local workers sparingly. They believed they could offer their customers a higher level of quality by relying on their own in-house expertise. Despite the distances involved, and concerned for their employees and their families, the company instituted a policy of whenever possible, bringing their people home on the weekends. As Randy Eisele stated, “Hire good people, keep them happy, and quality will follow.”

The company bread and butter began to shift to large transmission line projects in the mid-2000s. One hundred mile long alignments are not uncommon for power grid construction projects, and Tri-State had the equipment and expertise to accomplish such work. Unfortunately, these efforts pushed forward without the input of Wayne Riethmiller. Wayne died in 2006, but not before he was able to work alongside all three of his children at the same time, a situation that gave him great joy.

Tri-State Drilling Today

Jim was promoted to President when Wayne died. (Jim had also served as President of the ADSC from 2000 to 2001.) Bob has not officially retired, and, at 94, still comes into the office most days to look over the books, and read the field reports. Family members continued to walk through the Tri-State door, as Randy’s nephew, Anthony, joined the company as a civil engineer, and two of Gene’s grandsons came on board.

Tri-State Drilling today is a solid organization populated with people who get along with each other and even have respect and affection for one another. Each current member of management, whether it is Jim or Marylou or Randy or any number of others, speaks of their coworkers as friends and extended family.

Marylou Swedberg described the magic of the company in terms of the complementary attributes of the company’s founders. She said that each man had his unique qualities but each had values and principles that were similar to the others. Where Ralph may have been a people person and good with employees and customers, Wayne was a visionary and saw possibilities in new lines of work. Bob could identify good projects that were suitable for the company’s capabilities, and Clarence worked in a focused manner on keeping specific equipment running. They all worked hard and were united in believing that their employees should be treated well.

The current version of Tri-State Drilling is just a continuation of that magic. Marylou began her career as a directionally challenged

parts runner who created a map for successors to find the work sites that she (repeatedly) couldn’t find. She continues that model of resourcefulness in her role as Chief Financial Officer, developing ideas for maximizing company profits and efficiency. She works

across the office from her best friend and sister, Marilyn, who originally wanted to work in the field but wasn’t allowed to by her rather old-fashioned father. (She concedes that perhaps working on a drill rig might not have been the best environment for a young lady in the 1970s and 1980s). Marilyn works part-time, but is always there when she’s needed. Randy manages field operations, tracks job progress, and administers in-house education, and is passionate about the positive attributes of his co-workers. Jim provides balanced guidance for the company with a concentration on sound fiscal decisions and an understanding of new market developments. The many additional family members all bring different gifts to the party with similar views on how to work and live.

Corny analogies are almost inevitable in this story, where a strong network of four diverse, happy families is helping to build a strong network of electric transmission structures throughout the country. Even if the only beneficiaries of this hard work and conviviality were the families involved with the company, the straight-arrow business practices would be worth it. The effects of what the original company founders created are much more far-reaching and could be used as examples of how to think as “we” and not as “me.”